Rounds. Fast, rapid, run through, no regard for the patients, just the bare bones details. “He’s got a gangrenous toe. She has metastatic breast cancer. That one, well that liver cancer is killing her but the family doesn’t seem to get it. Yeah, that guy, he’s a real pain. Shipping him off to a nursing home. Oh, his roommate, he’s not ours, belongs to the AIDS social worker. Next. Oh, her, she’s crazy. Yeah, daughter’s nuts too. He’s homeless. Yep, another druggie. That other one’s hospice.”

I sit and listen, scribble notes, decide who to see, try not to condone the staff’s craziness while still being supportive… I’m their chaplain too.

I find out… oh no, I’ve really gotten to know that patient… here we go again – lymphoma and AIDS. Dammit. I wonder how many times between now and May I’ll be the chaplain for yet another patient with lymphoma and AIDS. Or actually, it’s AIDS and lymphoma. Or HIV+ and lymphoma. The virus is first, causing the conditions that can trigger the cancer. Whether it’s AIDS, well, depends on lab values, opportunistic infections… well, anyway, I read way too much of the science these days. Anyway, How many times have I seen this happen already during this CPE unit? And this patient, well, this one reminds me of… well, never mind, it doesn’t matter. But I’m self-aware. I guess that’s good. Know your triggers, right?

Rounds are over. I go to see the patient with the new cancer diagnosis. They’re glad to see me, and we start talking, trying to sort out all the new details.

My beeper goes off.

Emergency. Terrified young doctor. “Please send a chaplain, I need someone to be here when the spouse gets here.” Sudden, unexpected death of a young person. Oh no, this was the code I was always afraid of… but I have to go.

The medical team is pacing around, waiting for the family. To my astonishment some of the young residents are crying. It’s horrible, sudden, unexpected.

A meeting room, a husband on the floor, curled up, screaming. Who provides comfort when even the chaplain is shaken to the core?

The elderly Roman Catholic priest also heard the code, and arrives just at the right time. He has been doing this since before I was born. We divide tasks. I handle the medical team, he handles the family. Good. I’m not proud about this; I’m triggered, in over my head. We work for hours. I help the staff. I witness the priest’s work. I learn from a master. He later debriefs with me, explains his actions, seizes the teaching moments. I am grateful to this man, who so often takes the role of chaplain to the chaplains.

Back to the office. Tears. Repeat the story to supervisor and a colleague. Leave the hospital for fresh air and a late lunch.

Back to where I started at the beginning of the day. I go over the list. Let’s see, who has a new diagnosis? Who is on or nearing hospice care? Who did the staff say is having trouble coping? Who’s all alone? I sort through my self-created triage system, because I don’t have time for all of the patients on the floor. I try to see patients. This one’s asleep. That one’s at a test. This one’s being examined by the doctor. Over and over again, something keeps me from doing new work. Grace I think.

Finally, I end up in the room where I tried to start patient visits. I pull up a chair and we dig into conversation. We talk about how the patient feels about fighting lymphoma, what the staging means, what might happen. We talk about loose ends, getting things straight with God and other people. We talk about the patient’s experience of calling family, what they’ve been told, who freaked out, who’s okay. Some challenging words from the chaplain – about self-care, about not trying to take care of everyone else while you’re the one getting chemo.

The sun slowly sinks outside the window (it gets dark so early these days) and once again I listen to stories. It makes sense. A great deal of my philosophy of pastoral care is based on listening to people’s stories and helping them articulate where the current situation fits in, and what matters to them in light of all of it. So, like so many times before, with so many patients in so many rooms, I listen to stories about home, family, love and heartbreak, faith and rejection, other places, other times. As darkness descends on the city I hear a tale of a place a much younger version of my patient found magical, a small town kid in a big city, awed by the sights and sounds of a completely new world. And, for a while at least, lymphoma slips into the background.

And I head home where there’s dinner waiting (there’s nothing that consoles a tired and sad CPE student like food they don’t have to think about.)

The day is so overwhelming that I zone through my subway stop, winding up 10 blocks too far north. Sigh. After some extra effort I’m finally home where there’s a husband and dog and blessed good food. Shoes off. Collar off. Now.

Posted in Uncategorized

I spend a long weekend, Thursday-Sunday, on my first ever individual retreat.

I spend a long weekend, Thursday-Sunday, on my first ever individual retreat.

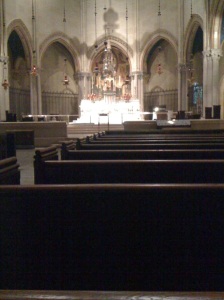

This place is engraved in my memory from a couple of visits during my first year in seminary. It’s darker and more hauntingly beautiful than my iPhone camera was able to capture. It also has a deep blue ceiling with stars. In more carefree times I had found it a bit dramatic and overwrought, with its huge statues and icons, its row upon row of flickering candles in the various chapels and nave. It had lived in my imagination as an interesting and quirky yet enchanting place, alluring but ultimately not really for me.

This place is engraved in my memory from a couple of visits during my first year in seminary. It’s darker and more hauntingly beautiful than my iPhone camera was able to capture. It also has a deep blue ceiling with stars. In more carefree times I had found it a bit dramatic and overwrought, with its huge statues and icons, its row upon row of flickering candles in the various chapels and nave. It had lived in my imagination as an interesting and quirky yet enchanting place, alluring but ultimately not really for me.